Product Management Webinar: Product Discovery

Uncover the Secret to Continuous Product Discovery

How do you achieve continuous product discovery?

Join our fireside chat with special guest, Teresa Torres, Product Discovery Coach, speaker and acclaimed author of “Continuous Discovery Habits”, and host Janna Bastow, CEO of ProdPad and inventor of the Now-Next-Later roadmap.

About Teresa Torres

Teresa Torres is an internationally acclaimed author, speaker, and product discovery coach.

She teaches a structured and sustainable approach to continuous discovery that helps product teams infuse their daily product decisions with customer input. She’s coached hundreds of teams at companies of all sizes, from early-stage start-ups to global enterprises, in a variety of industries.

She has also taught over 7,000 product people discovery skills through the Product Talk Academy and is the author of her new book “Continuous Discovery Habits“.

Key Takeaways

- The mindsets required for your team for succeed with continuous discovery

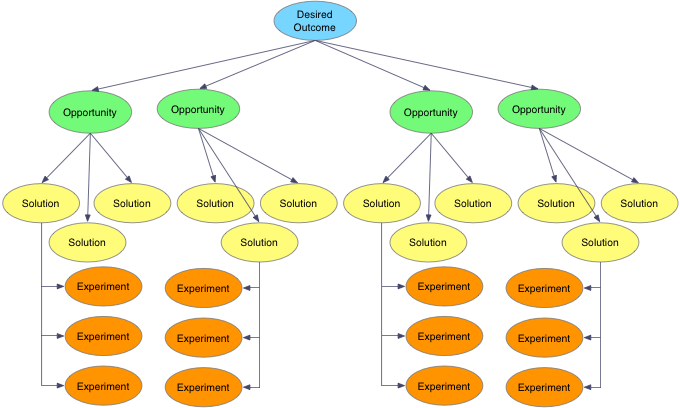

- How to use the Opportunity Solution Tree to generate better ideas

- Using interviews, prototypes, experiments and more to evaluate your solutions

- Aligning your team around a shared understanding of your desired outcomes

[00:00:00] Janna Bastow: Hello everybody. Welcome. Welcome. Come on in, you’re joining us here at the ProdPad Product Expert webinars, and the reason we call them that is because we have a different expert each time. They always come with different insights and the focus is always on the content and the learning and the sharing.

The past talks are recorded, so you can go see those on our site. And what we do is either presentations or just fireside chats, like today’s going to be, so today is going to be recorded and shared, and you are going to have a chance to ask questions.

Before we dive into things, let me just tell you a little bit about ProdPad, which is what we do.

This is a tool that was originally built by myself and my co-founder and we were product managers ourselves, and essentially we just needed tools to do our own jobs. We needed something to keep track of the experiments we were running. We needed something to help keep track of the objectives we had and how we were going to solve our customer problems, and just keep tabs on all the ideas and feedback and everything that made up our backlog.

So building ProdPad gave us the control, and the organization, and the transparency that we and our team needed. And it wasn’t long before we shared it with the product people around us. And so today it’s used by thousands of teams around the world, and it’s free to try.

And we even have what we call a Sandbox mode, where it has example product management data, so you can see how, lean roadmaps, OKRs, experiments—how it all sort of fits together in a product management space. Our team is made up of product people, so, start a trial, let us know how it works. Give us your feedback.

Today is actually going to be a really interesting conversation because I love talking about discovery, because ProdPad at its heart is a discovery tool. We’ve reframed the roadmap from being a tool that essentially holds you back and holds you to dates you never really wanted to commit to in the first place, to being this place where you outline the problems and the opportunities that you might tackle and helps you track the experiments and the outcomes that you’re learning from along the way. So we’ve really helped rethink how product management can be used for more of a discovery type of process than purely delivery.

So jump in, give ProdPad a try and let us know how you get on with it.

And in the meantime, I want to jump in and introduce our guest for today. So this is Teresa Torres. She’s an internationally acclaimed author, speaker, product discovery coach, you probably know her as the author of her new book ” Continuous Discovery Habits”, which she’s got a ton of them behind her there. I’ve got just one of them right here with me. Great book, highly recommended. She’s taught over 7,000 product people discovery skills through her Product Talk Academy.

And she’s actually here today to talk about how to build a continuous discovery habits. So everybody say welcome, say hello to Teresa and, from me, welcome Teresa! Thank you so much for joining us here today.

[00:02:47] Teresa Torres: Thanks Janna! Thanks for having me. I’m super excited to be here.

[00:02:50] Janna Bastow: Yeah, absolutely great to have you here and great to have a chance to chat with you, I think back to when we first met you inducted me into SF, you’re the first person to take me to Blue Bottle coffee in San Francisco.

[00:03:01] Teresa Torres: Yeah! So you had your introduction to San Francisco sort of third wave fancy coffee.

[00:03:08] Janna Bastow: Yeah. We met up, then we had a properly geeky conversation about product and discovery and things like that. And that was going back like some many years ago now.

Yeah. But probably worth giving some people here an idea about your background, anything that I might’ve missed, to get everybody on the same page here.

[00:03:25] Teresa Torres: Yeah, you did a pretty good job. Probably for the last kind of, depending on how you count for the last 8 to 10 years, I’ve been working as a discovery coach, really just helping teams make better decisions about what to build. That work has evolved in that time period because our discovery methods have evolved.

It’s been actually really fun to see. I know that 10 years ago, the prominent conversation in product was user stories and managing backlogs, and it was all really grounded on the delivery side. And it’s really fun to see the whole industry, embrace discovery and recognize that customer centricity is a big part of the work that we do.

And before that I did, what a lot of probably listeners are doing, as I held different product management and design roles at different early stage startups. I ended up in some leadership roles. I ran a startup during the ’08 economic downturn, which was one of the most challenging things I’ve ever done.

That actually directly led to me becoming a coach because I realized being an executive was not the best fit for me. And really what I was passionate about was helping to develop a really customer centric product. So here I am.

[00:04:35] Janna Bastow: Excellent. Yeah. And you’re an excellent coach, I know that from the stuff that you’ve been putting out, that you’ve taught so many people and you ask really good questions.

This is one of the things that I like about the book that you’ve published, is that it helps product people ask those types of questions of themselves and take a look at the habits that they do have.

You want to tell us a little bit about this book that you’ve recently published?

[00:04:56] Teresa Torres: Yeah, so I think we’re at the point in the industry where most individual contributors in the product space know about discovery, they want to do it. But we have very few companies that have a strong culture of discovery. And so the challenge is you could be eager and willing, but you don’t know what good looks like.

And so I recognized this problem a few years ago, I started writing on my blog, trying to write about teams that were working this way, just to paint a really clear picture of what does good look like. And then I started to notice that like, when I would work with coaching teams, they would come into our first session and they’d say, Hey, we already do continuous discovery.

And then we’d get into their tactics. And they were doing a lot of discovery activities, but they’re still doing them from this big project mindset—in bursts. And I just recognized that really there’s just a know-how gap. It’s not a, we don’t need another why we need to work this way book. We just need to paint the picture of what does the day-to-day look like and teach me how to do it.

And so that was my goal in writing the book was to give a practical how-to guide for a product trio to really start to adopt these habits, and really change the culture, starting with their own team.

[00:06:06] Janna Bastow: That makes a lot of sense. And so you mentioned this product trio, who is the product trio?

[00:06:12] Teresa Torres: Yeah, I didn’t think this was a controversial topic, but since the book has come out, I have learned it is kind of a controversial topic. So I defined the trio as a product manager, a designer, and a software engineer working together from the beginning to make decisions about what to build.

And I’ll contrast that with what we’ve historically done, right? Historically, the product manager gathered requirements or wrote a Product Requirements Document (PRD), or even user stories, handed them off to a designer who did the design work, and then the requirements and the design got handed off to engineers who implemented.

And what we saw with that, basically, even if you were doing Scrum waterfall model was a lot of lost context and nuance and a lot of rework. And so we’re starting to recognize that, like, these are three critical functions for collaborating on what to build. Let’s just get them together from the beginning, let’s get them engaging with customers from the beginning, so that we just get better solutions and we meet and we build better products.

The reason why this has become somewhat controversial is that, as we see discovery become more important in companies, we’re seeing a bigger like specialization and diversification of roles, and so I’ve heard from a lot of people about like, Hey, I’m a user researcher. Why don’t you include me in the trio?

Or I’m a UX writer or I’m a data analyst, so I will say the trio is not designed to exclude anybody. The idea really is flexible based on the roles available to you on your team and the types of decisions that you’re making. It’s just a trade off, right? Between speed of decision-making and quality of decision-making.

So the speed, fewer people involved in the decision, the faster you’re going to go quality, you want the right cross-functional roles represented. So you’re leveraging the expertise on your team. And so the idea flexes based on who you have and what type of decision you’re trying to

[00:07:57] Janna Bastow: So the product trio could differ based on the context of who’s already in the team as well, right?

[00:08:03] Teresa Torres: Yeah. So I’ve worked with teams where maybe it’s a really data heavy machine learning based product. They probably have a data scientist on their trio, that’s now a quad. Some people argue that those types of teams don’t need UX. And I disagree. I think everybody needs a UXer.

Or let’s say a team is a trio most of the time, where they’re starting to do discovery around their go-to-market strategy, they might invite their product marketing manager to be a part of that discovery for that subset of discovery work because they have expertise they can leverage, right?

The big one I get all the time is, My company’s investing in user researchers. What role do they play in a trio? And it kind of depends. If your user researcher is full-time embedded on your team, so they’re not going to be a bottleneck, you have a quad and that’s awesome because your user researcher is going to really help you with a lot of those decisions, and is really going to help you with getting collecting more reliable feedback throughout discovery.

Most companies don’t have that many user researchers and that’s a shared resource. So now if we include them on our trio, that person will be the bottleneck and will slow the team down. So I don’t recommend if they’re a shared resource, putting them on your trio, you need to still consult them when the decision is relevant to them.

So that’s this idea of it flexing, is that your trio can grow and shrink based on the types of decisions and the types of roles on your team.

[00:09:24] Janna Bastow: Right. That makes a lot of sense. And Kim in the chat just asked a question. What role does sales play discovery? Do they have a place in this trio?

[00:09:33] Teresa Torres: I’m a firm believer that good sales is the same exact thing as good product discovery. So what are we doing in discovery? We’re trying to uncover unmet needs, pain points, and desires. What should a good sales rep do in the sales process? Try to uncover unmet needs, pain points, and desires, and then show how your product addresses those unmet needs.

So I would love it if this idea of the cross-functional product team started to grow, to include our business roles. Very few companies are there, right? We’re just starting to talk about like agility across the organization. I think the product mindset is what our business mindset will eventually be.

I really think the way product teams work is the future of business. But I don’t think we’re there yet, anywhere close to there.

[00:10:20] Janna Bastow: Yeah, that makes a lot of sense. I hear people talking about the problem that they have, where their sales team is constantly selling stuff that they don’t have, right? They need to have a roadmap. They need to be able to deliver on that roadmap because the sales team is expecting it, because they’ve made these commitments of things that need to be built in the future in order to keep the business up and going . And the way that I’ve always started turning that around is to point out that the sales team should be selling what you have, right?

You should only sell what you have and not what you don’t have. And if the sales team can’t sell what you have, either your sales team isn’t good enough, or your sales team is really doing the wrong job, right? If you don’t have anything to sell today, your product literally doesn’t have the features and it doesn’t have what you need, then redeploy them as researchers. Get them out there to help you figure out what kind of things could be needed by the market.

[00:11:08] Teresa Torres: Yeah. I see a lot of parallels between sales and product. So if we look across the industry, the vast majority of product teams are solution-first. We’re very solution focused. We live in output world, which is why we have analogies like Feature Factories and Melissa Perri’s Escaping the Build Trap, right?

We have a culture of starting with ideas and starting with solutions. The best product teams are moving away from that and focusing on outcomes and focusing on value. In my world, I call them opportunities. Customer needs, pain points and desires. We see the exact same parallel on the sales. Your average sales team is selling features, selling solutions and they’re selling today’s solutions and what they think tomorrow’s solutions are, and that’s where they get into trouble.

I think the very best salespeople are selling not a solution, but a possibility of addressing a need. So it’s less about “here’s this widget”, it’s more about “our product or solution will address this need”. And then what that does is it gives the product team the leeway and the flexibility to figure out the best way to meet that need, rather than this really off the cuff prescribed solution that occurred on the fly in the sales meeting that probably wasn’t the most well thought out solution.

I actually do think some salespeople do need to sell beyond what your product currently has. This is particularly true in early stage startups, right? Your sales team is your missionary. So you’re selling the vision of the product.

And I don’t think there’s anything wrong with that. As long as it’s aligned with the product team’s vision of the product, and it’s a vision, it’s not a list of features.

[00:12:49] Janna Bastow: Yeah, exactly. And that’s the key thing is, you know that iron triangle of scope, time, cost, sort of thing, right?

They can’t sell this, the scope and the time and the cost and say, this is what you have to go deliver to. Because at that point in time, you’re going to lose the quality. That’s where you tend to get in trouble. If they’re willing to say, actually we’re going to give on the scope, but what we can do is say that we can solve this problem for this type of cost, right? We validated this is in fact, a problem worth this much to this type of customer, but you figure out how you go about doing that. That’s actually all we really wanted. That gives us lots of room to go figure out how to solve that.

And, there’s lots of things that our product team can do with that information.

[00:13:27] Teresa Torres: You’re making me think of, probably the best thing I’ve ever said on a stage from an audience reaction standpoint, and I loved it so much, I put it in the book as well, which is during my talk at Mine the Product San Francisco.

I said, and it was off the cuff. Martin had told me right before I went on the stage that I had more time than he had originally told me if I wanted it. So I added a little bit at the end of the talk and I said, you’re not one feature away from success. And it literally, like I’ve never received an audience reaction like I received that day. It was unbelievable. And I think it’s because that resonates, like we product teams have such a strong belief that this next release, this next feature is just going to solve the world. This is directly analogous on the sales side. A salesperson has the same belief that this one feature that the customer is asking for is going to close the deal.

And it’s really poisonous on both sides because that’s not really true what we need to learn. Both the product teams and salespeople is that that feature request represents an implied need and that we have to do the work to uncover that need and find a better way to solve it.

[00:14:36] Janna Bastow: Yeah, that makes a lot of sense. Excellent. So actually you mentioned something, you said you call them opportunities and I wanted to ask about that, one of your concepts that you’re best known for is the Opportunity Solution Tree. And I don’t know how many people in the chat here are familiar with the Opportunity Solution Tree, but maybe you want to tell us a little bit about that work. How did this come about and how are you seeing it?

[00:14:58] Teresa Torres: Yeah, so I hate jargon and I really hate that I’m part of creating jargon in our industry. So I’m going to apologize for the ‘Opportunity’ of language. I didn’t invent it. It was already in use. I just borrowed it. But, and I think it’s important, I think the reason why we call them opportunities and not problems is really important.

So I don’t completely regret it, but Opportunity Solution Tree is a terrible name. It should’ve been called ‘outcome map’, but whatever, I’m over it, it’s out there. It’s a thing. So let’s break this down a little bit. So most people are familiar with this idea of the problem space and the solution space.

So the problem space is, how do we really get clarity around what problem we’re solving? How do we make good decisions about the most important problem to solve? I think it’s really easy for product teams to have this bias towards our job is to fix things and to solve problems. And that’s part of the equation.

We do do that, but we also build things that address desires that create delight, that create joy. And so the examples that I give are like, I really like ice cream. Ice cream does not solve a problem for me. In fact, it creates more problems than it solves. But, my life would be less awesome without it.

And I want that product to exist in the world. So it’s like a really good example of a product that’s not solving a problem. It’s addressing a desire. Right? Entertainment products, usually don’t solve problems. I mean, we could kind of stretch it a little bit and say like, I need to fill my time. Come on really, like I’d be better off going and working out or doing some work than being entertained.

So I think the idea of the language ‘Opportunity’ is to get you to think beyond just fixing problems and looking for opportunities to positively impact your customer’s lives, whether that’s by entertaining them or creating delight, or by addressing a desire. So it was meant to be more inclusive language.

It’s a little bit of a barrier and the real problem with the word is it conflicts with business opportunity and that’s not, they’re not the same thing, right? So that, so the language is a little messy and I apologize for that. The Opportunity Solution Tree visual is designed to help teams chart the best path to an outcome.

So most product teams start with, ‘I’ve got a fixed roadmap. I got to deliver these features by this timeline. And even though we’re not good at meeting timelines, we are good at delivering features’. And so that was a very clean lines, easy world. Put your head down, grind out the work.

Now we’re asking teams move this metric. Figure it out. That’s a completely different way of working. It’s a wide open unstructured problem, and we need a way of putting structure to that problem. And especially when you’re doing it collaboratively as a trio and staying aligned as a team about how we’re tackling this challenge. And so the Opportunity Solution Tree helps you map out what are the opportunities, the needs, pain points, and desires that we’re hearing in our interviews so that we can get a big picture view of all the ways we might reach our outcome.

And then, it also helps you align, make sure your solutions really do address the opportunity you’re trying to solve. And then also keeps track of the assumption tests you’re running, to help you evaluate those solutions. So it’s really just a visual diagram to make sure that you’re working in the right scope and you’re staying aligned.

[00:18:15] Janna Bastow: Yeah, that makes a lot of sense. One of the things I’ve always loved about the Opportunity Solution Tree is that it gets teams out of this habit of getting stuck in the details of trying to prioritize at the solution level. Or as you say, falling in love with their idea. It’s so easy to just say, well, this is the right solution. This is the one. And it sort of blinds them to all the other things. And the Opportunity Solution Tree helps identify where it sits amongst all the other things. And so, if it’s just sitting there and it doesn’t actually solve an opportunity, doesn’t have an opportunity that it sits neatly with, or if it’s sitting there and there’s no other potential solutions you’re like, are you sure that’s the only way you would solve that? Or is that not tied to an outcome? If you can’t tie your solution to an opportunity into an outcome, why is it there?

[00:19:05] Teresa Torres: And if you think about it, that’s I think one of the big benefits. Ideas are cheap. We have a million ideas. I love one of my favorite things to do. It’s kind of mean, but I feel like you got to have this lesson at some point, is I meet a startup founder that’s like totally in love with their idea. And I want to just rip and come up with 20 alternatives. Like yeah, your idea is great. Here’s 20 more. And it’s because we have this such a strong culture of like, it’s about the idea we have this creative myth, that beautiful idea is just born, that’s not true, right?

Good products start out as really crummy ideas that we iterate on, and blood, sweat, and tears over to really turn it into something. And I think that work is driven by understanding the opportunity space.

The one thing I wish I could tell everybody working on digital products is that ideas are cheap.

It’s not about the idea. It’s about the outcome you’re trying to drive and the opportunity you’re trying to address. And honestly, you could generate a hundred ideas tomorrow if you really had to.

[00:20:04] Janna Bastow: Yep. And this is what’s always bugged me, is that all of our prioritization solutions for the most part are all tied around prioritizing ideas, like RICE and ICE and weighted scoring and stack ranking, and all these things are all about taking these ideas and shuffling them around. But if that’s not the biggest problem or opportunity for your business, then the real one might be over here at which point you’ve just reshuffled a whole bunch of things over here. It’s like fixing the pixels on a button that isn’t even the right button.

[00:20:32] Teresa Torres: And there’s a kind of double whammy here. Not only are we just having the wrong conversation, like we’re missing the strategic question of where should we even be playing, but also all humans fall in love with ideas. It’s just how our brains work. Like ideas are shiny and they’re exciting and they’re new, and so it’s also where we’re going to have awful opinion battles. And it’s also where we’re going to see the HiPPO come in and dictate what we should do. And it’s where all the mess is. And it’s actually where we spend 90% of our time. And I think we need to flip that on its head. I think ideas are cheap.

Ideas are the easy part. The real work is really understanding how we’re going to create value for our customers by discovering opportunities and really understanding how we’re going to create value for the business by setting good outcomes and aligning those two things. Yep.

[00:21:20] Janna Bastow: Yep. Somebody actually asked, what language for the elements and the tree would you choose now if you could go back in time?

[00:21:26] Teresa Torres: I think ideas are simpler than solutions. I think the problem with solutions is people think big, project-based solutions. And I want you thinking about really teeny tiny solutions for a very specific target opportunity. I’m not changing it. It’s out there. It’s theOpportunity Solution Tree, so that’s the first thing, but I do think idea maybe would have been better than solution. I don’t have a better word for opportunity, but now that I’m like doing a virtual tour and I do a talk every day. Seriously, the number one question I get is what’s an opportunity, even though in my talk, I did define it like seven times.

Every time I say the word opportunity, I say, it’s a customer need pain point or desire. And then I still, in the Q&A, get a question about it so I can tell the language is a barrier. And that’s one of my personal goals in my blog, writing in the book, is I’m trying to make these ideas as accessible as possible because I don’t believe in obfuscating things through like horrible business jargon and even an outcome is jargon.

But here’s what I’ll say. I do think outcomes are important and I do think opportunities are important. I think these terms are going to become part of our vernacular. They’re going to become accessible. And so I’m not losing sleep over it. Talking about this literally every day, since the middle of May has made me acutely aware that not everybody has the handle on the language.

[00:22:48] Janna Bastow: Yeah. That’s totally fair. And actually funny that you mentioned moving from, solution to ideas, I mean, take it from me. I built a tool called ProdPad and we have Ideas and we had a huge discussion years ago, about whether we’re going to call them ideas or something more nebulous or whatever, and sometimes I have regrets going, maybe we should call them experiments, right. People away from this shiny idea, and solutioneering type of stuff. But they’re ideas for now.

[00:23:14] Teresa Torres: That’s interesting because, a few people have noticed this, that I need to clean up my artifacts, but I have moved away from experiments. So on the original visual of the Opportunity Solution Tree, it’s still says experiments. And if you go to Product Talk, it still says that I have not cleaned it up, but in the book I moved from the language experiments to assumption tests. And for a very specific reason. So most teams, when they hear experiments, they think large quantitative A/B test. And that’s not the experiment I want you to starting with.

And we forget that the goal is to test a very specific assumption and not the whole idea. So I shifted to the language assumption test to remind you, you are testing a specific assumption and it’s much smaller than this idea of a scientific experiment. So it’s really interesting. It’s really deepened my thinking about language and what we’re trying to communicate and what people need as they’re doing this work to remind them of their focus.

And I had originally chose solution because I started with problem space, solution space. That’s a concept that already exists in the world. But I do think that, over time, it’s really important that we continue to sharpen the language and really help people set the right scope for their work.

[00:24:30] Janna Bastow: Speaking of language, somebody in the chat just asked the question HiPPO?, and I think it is something that a term that we use in our space. And I don’t think it is universally known. What does HiPPO mean?

[00:24:45] Teresa Torres: So the HiPPO was a horrible acronym because it’s HIghest Paid Person’s Opinion. So technically the H and the I come from highest, but the concept represents this idea of a product team does great work or whatever. And then the CEO or some other business stakeholder helicopters in and said, No, we’re going to build this and they’re the highest paid person in the room. And so that’s who gets listened to.

[00:25:09] Janna Bastow: Yep. That makes sense. There’s now chat going on in there about some terrible acronyms people complaining about Minimum Viable Product and Minimum Viable Experiment.

[00:25:17] Teresa Torres: Those acronyms do not appear in my book and and very deliberately. I want to call out because, I think it’s Adeep, just highlighted that it seems like I’ve been performing continuous discovery all my life, even with readers and viewers. And here’s what I will share.

I remember in 2011, when the Lean Startup came out, I was, see if I can do some math. I was 12 years into my career. All of it was early stage startups. I read that book and I was like, wow, somebody is finally writing a book about how I work. Ever since then, my focus has been, how do I develop and refine these practices?

And I really do think that for me, the reason why this has been such a good fit is it is fundamentally how I think like, it’s really like, I do everything this way, but I was trying to figure out where to live. Like I was in the San Francisco bay area. I was over it, that place. Got lunatic, insane. I needed a new home.

I went to four different cities to try out living in different cities. Because moving is a big waterfall, permanent decision. And that to me is really important because what it allows me to do is I feel like I get to show up authentically as myself in all of the work that I do. And even the book, like even writing the book, I was like, this is just, explaining how I think. So, thank you for acknowledging that because that’s very true.

[00:26:40] Janna Bastow: Excellent. Yeah. And I just read your article about how you did continuous discovery on your book, and followed that flow, which makes a lot of sense. And I know you’ve been writing about this topic for a long time and I know from our past chats, this stuff has been coming together for a long time.

Excellent. All right. When working with early stage startups who should be leading continuous discovery when there isn’t somebody leading products, is that the CEO COO, we were talking about micro startups here.

[00:27:06] Teresa Torres: Yeah, startups are hard. Startups are hard. I love startups and I love founders. I feel like to take that kind of risk and to really believe you can change the world by starting from scratch is an amazing thing. And 98% of founders are solution-focused and not customer-focused.

And early in my career as a consultant, I wanted to work with startups because that was my full-time employee experience. And I very quickly moved away from it. And it’s because founders are really ego-driven and that’s a good thing and a bad thing. The good thing is, is that it convinces them to change the world and to take risks and to do things that most of us would not do.

And the bad thing is, is it’s a giant blinder to serving your customer. Now, there are, I would say there are probably 2% of founders that are truly customer centric. And instead of—maybe it’s higher than that. I’m just kind of cynical —is that they truly start with a cost target customer segment, a value proposition, and they iterate their way to the right solution. And that’s amazing.

So that’s the first thing is that like a lot of people ask me, how does this process work in a startup? If you have a very solution-focused founder. It’s going to be really hard to be outcome driven and to really understand the opportunity space. It doesn’t mean you individually can’t do it, but you’re going to have a hard time getting your company to rally around it because in a very solution-first context, it’s really hard to change that culture, but you can still do the whole second half of the book.

You can still story map your ideas, break them down into underlying assumptions, run assumption tests, catch the gotchas before you ship them out the door. So it’s not hopeless, right? You can still do all that work. But I think the heart of the question was you’re a five person startup team. Maybe you have a CEO, some engineers, a designer, hopefully.

Who’s on the trio. I would say most of the time, your founder is the product manager. And what’s hard is does that person have the ability to let go of their baby if they learn the baby’s wrong? And that’s the hard part of startups. My experience is that first time founders need to fail before they’re willing to get away from, ‘I have this brilliant idea. It’s going to change the world.’ And that’s unfortunate. I wish we could change that, but it’s going to take a pretty big culture change.

[00:29:23] Janna Bastow: I’m also thinking like the product trio can help keep you honest. If you’ve just got one person who’s running the company and says, you know what, I’ve got this idea and we’re just going to hire some people and get some funding to go do it.

You’ll end up going to do it like that is possible. There are lots of ways to just build a bunch of stuff and get it out the door, but having a product trio, having a group of people who work in this way, this continuous discovery process is all about figuring out what those assumptions are and checking those assumptions.

And if you’ve got multiple people around you who are there to bash apart your own assumptions and each other’s assumptions, you’re less likely to fall prey to your own biases.

[00:29:58] Teresa Torres: So I do think discovery as a team sport. I think the reason why this idea of the trio is taking hold is because we don’t see our own assumptions.

So the more diversity you have in the room, the more likely you’re going to cover more assumptions, the more likely you’re going to catch your gotchas before you release. I would love it if we could get to a startup culture where we have a trio is the founding team, right? It’s not just about the one.

Again, we culturally have this really strong myth in the lone creative genius. Right. We see this with Apple, with Steve Jobs. And Steve Jobs, maybe he was a creative genius, but he also had a creative genius in Johnny Ives with him, his designer. And I’m sure there’s an engineer that was elevated at that level because their hardware manufacturing is first-class.

I’m sure we have the same myth with Elon Musk right now. We have the same myth with Jeff Bezos, although as Amazon matures, we’re recognizing there’s a lot more people that were involved in the success of that company. And so I think that’s part of it is that we have to move away from that myth and recognize that building companies and especially, doing good discovery work is a team sport.

It requires multiple roles—it requires multiple perspectives.

[00:31:07] Janna Bastow: That’s a really good point. I’ve said to people before, like you’re not Steve Jobs and actually, Steve Jobs wasn’t even Steve Jobs, this idea of somebody on a pedestal, but you know, he didn’t do this alone and he had amazing people around him.

[00:31:20] Teresa Torres: I would argue Steve Jobs’ first Apple, he was trying to be the lone creative genius and he got pushed out of his company.

[00:31:27] Janna Bastow: That was his first fail that you talked about. Right?

[00:31:31] Teresa Torres: Yeah. And I think because of his work with Pixar where they have an amazing collaborative culture, and then, his work at Next, I know it was also a much more collaborative engagement. And so as a result, he comes back to Apple, and I think what we see is a much more collaborative approach. Still the like amazing standard of quality, which I think was his real superpower, which was, we are not going to release something that we’re not entirely happy with, it meets this ridiculous standard. And that’s, I think what truly inspired people to, as he say, put a dent in the universe, right.

[00:32:03] Janna Bastow: Yeah, that makes a lot of sense. That’s actually really key, building these MVPs or these tests or whatever it is, whatever you want to call them, doesn’t mean shipping things of low quality, right? A lot of companies try to get away with just shipping something fast and cheap and terrible, and then saying, oh, well it didn’t work.

We’ll go back to my idea. And that’s not what it’s about. You still have to have the quality there, but in order to have the quality, you have to sometimes, slow down and spend more time in discovery, more time thinking about how you’re actually going to build and deploy something and actually less time in the delivery cycle than you actually imagined.

[00:32:39] Teresa Torres: Yeah. This is one of the things, the Opportunity Solution Tree has helped me with a lot. And that’s that it’s really hard to communicate this idea of we’re talking about agile or MVP or starting small, or getting into the heart of the idea.

People interpret that as low hanging fruit or the crummy first draft. And it’s like, we’re taking this quality hit. And I don’t think that’s the idea at all. And this is where I think the Opportunity Solution Tree helps. The opportunity space onOpportunity Solution Tree is structured in a tree structure.

Here’s what that gives us. The opportunities at the top of your tree are big, hard evergreen opportunities. So the example I give is a Netflix example. Netflix probably has this evergreen opportunity. If I can’t decide what to watch, no matter how long Netflix is in business, they’re going to be trying to solve that problem.

Right. I can break that opportunity down into smaller and smaller opportunities. So I could say, why can’t people find what they want. I don’t know how to search for a specific movie. I don’t know if this show you recommended is good or not. I don’t know what my friends are watching. I don’t know what kinds of things I like.

Right? Like those are all sub opportunities. I could take something like, I don’t know if the show is good or not, and break it down even further. How do people decide if a show is good or not? Who’s in this show? Is it like something I’ve seen before? Does it have good character development or is it plot driven?

Right? Those are all sub opportunities. Now when we get to a sub opportunity, like who’s in the show. That’s a really small opportunity that we could design a really elegant high quality solution in a couple of weeks, but that’s not a hard thing to build. And so what that does is it gives us a teeny tiny starting point.

We’re fully satisfying a small opportunity and satisfying that small opportunity helps contribute to solving the higher level opportunity. It doesn’t solve it entirely, but it helps to contribute to it. So it helps to unlock this continuous cadence where we’re looking for iterative as small pieces of value that we can deliver where our quality stays high, but we’re unlocking this continuous cadence.

[00:34:44] Janna Bastow: Yeah. That really resonates. And I like how you talked about the fact that the opportunity won’t entirely be solved. Cause I think that’s true for so many cases. And this is one of the things I come across when people talk about the roadmaps with me is, if I put this on the roadmap, at what point in time does it come off the roadmap? Or what point in time is it solved? And it’s like, well, you don’t have to do everything. You don’t have to 100% solve every problem. Your job is to minimize the problems or maximize on opportunities. And then move on to the next thing, because if you’ve minimized a problem, then chances are the next problem is now bigger and relative order. And so you can move on to the next problem. And, eventually you might come back to that problem of that is then, the place that you optimize and that’s where you get to companies where they start optimizing, like the micro pieces here and there, but don’t get tied up and trying to micro optimize something, trying to finish off every last tiny piece, if there are other problem to go solve.

[00:35:39] Teresa Torres: Yeah, I think you’re spot on.

So this is also where I think having the visual of your primary goal is to drive your outcome. And when you’re assessing in the opportunity space, your assessment is which opportunity do we think will have the biggest impact on our outcome. And when you release a solution, you have to go back and reassess, okay, we’ve changed the landscape.

We put a new solution out there, which means that opportunity may no longer be the most important opportunity for us to work on because our customers might be satisfied enough that now there’s a more important opportunity. And so I like to see teams like literally after every code change, go back and reassess because you may, yes, there may be more work to do on that opportunity, but it may not be the highest impact place to work.

If your goal is to drive your outcome.

[00:36:28] Janna Bastow: Yeah, absolutely. And this is exactly why roadmaps should be flexible, right. They’re designed to be bashed apart every time you change something major, right? So you push something, you solve a problem, even part of the problem. You look at the list of problems again, you go is this still the main problem? Or actually, should we shuffle this back to the back of the list and go work on the first one? Somebody just asked the question, how could this flow be run in ProdPad? And this is how the Now/Next/Later lean roadmap is mapped.

It maps very much closely to the, the Opportunity Solution Tree, where what we call initiatives on the roadmap are opportunities, problems to be solved or opportunities, and you can attach ideas or solutions, each opportunity is attached to outcomes or what we call objectives.

And you can see how it all maps together. And if one of those opportunities moves, you can drag and drop it. You can see where they all sort of sit and flow with each other. So if anybody wants to take a look at that, happy to walk you through and, give you a demo, show how it all fits together in context of this tree.

[00:37:24] Teresa Torres: I’ll also share that, this past January on Product Talk, I shared a subset of my roadmap and I did it using the Now/Next/Future format. And the way it works is now, next, and future all had opportunities, right? So I have a Now opportunity. I have a Next opportunity and I have a Future opportunity.

Now also had a solutions in flight. I think Next had some ideas of what the solutions might be. I think Now actually even had some release dates. Like I think one of them—my Now opportunity was, at the individual contributor level, I need to know what to do when in discovery—and one of my solutions in flight was the book.

And I think I had a release date by that point. And then the other opportunity, the other solution in flight, which I don’t think I announced the details of in January was our membership program that we launched with the book. And then in the Next column, I had a different opportunity, my Next opportunity was, I’m an individual contributor and I wanted to build up skill in a specific discovery habit. So we have online courses in defining outcomes. It continuous interviewing and an opportunity mapping. And I’ve had on my roadmap for over a year now to launch courses in identifying hidden assumptions and testing assumptions.

And my plan was to get those out by the end of this year. So that was my next opportunity with solutions in mind, but no dates because I’m not working on them right now. I don’t have release dates. The audible version of my book is probably in that category as well. People keep asking me when it’s going to come out, I want to narrate it myself. I need a chunk of time to do that. God knows when that’s gonna happen, hopefully by the end of the year. But I can’t commit to that because it’s not in flight right now. Right. And then my Future opportunity was I really want to help leaders learn how to manage teams who are working with. I have no idea what solutions I’m going to build for that opportunity, because in the future, I haven’t even started thinking about it.

And what I like about that format is that you stay focused on opportunities, which is what really matters. But in the near term, you can give visibility to what’s in flight and when you might be releasing things, so the rest of the organization can plan around it, but you’re also communicating there’s a lot of uncertainty. Yeah.

[00:39:33] Janna Bastow: Yeah, that’s exactly right. And that’s why the Now/Next/Later works, it’s mapped to some people might’ve seen the cone of uncertainty charts. And that’s really where, one of the concepts that was built into the Now/Next/Later when we first built it, which was this idea that things that are close to you or things that you can see you’ve got granularity, you know how close it is or something that’s really, really far flung, you don’t know how far away that is. And it doesn’t actually really matter right now. Cause it’s not about to hit you in the face.

And somebody actually just asked, Ryan just asked us , for the Now/Next/Later, is there an expectation for dates in the Next column? And you know what, it depends, we don’t live in Lala land.

We don’t live in a world where there are no dates. Right. Sometimes there are dates that are inflicted upon us. We like to think that companies can be fully discovery led. And if we learn something interesting, we can all pivot tomorrow. That would be great. But we do have constraints and commitments and other things that sometimes mean that we end up having to move in certain directions.

Like for example, if there’s a new privacy law, like when GDPR landed, everyone had a card on the roadmap that had that date. You had to have something ready for that. But it doesn’t mean that just because you have a date for one thing that you have to force yourself to put dates for everything.

So you might put a date on something just to tell the team and communicate that, but don’t force yourself to put dates on everything, if you can actually take advantage of and be, more discovery-led.

[00:40:56] Teresa Torres: I also think we think of dates as bad. And I think there’s a distinction between a hard date and a soft date. GDPR was a hard date. It was a regulation. We had the follow and that you can’t even change the scope. You got to follow the law. I mean, there’s a little bit, you can change the scope, but you can’t change the scope beyond what the law requires.

And so I think that’s an example of a hard date. You got to rally the troops, everybody’s all hands on deck, whatever analogy you want to use, you have to hit that date. I think we also need to get better at recognizing like soft dates can be helpful because again, they allow everybody to plan and to coordinate efforts, but building software is complex and those dates might change.

I saw this in my business. If you had asked me in January, when I was going to launch my identifying assumptions and testing assumptions courses, I would’ve said June right after the book comes out. What I didn’t forecast was by June, my course business would have grown tremendously—It’s the upside of COVID—and my course infrastructure, which literally was put together with duct tape and shoestrings, was falling apart. And that I was going to spend my entire summer being a software engineer again, fixing my infrastructure problems. Right. So instead of getting to do course design, I got to become an engineer and I’m now literally rebuilding all of the software that underpins my business.

And that’s great. I feel now that we’re in August, I feel great about that. Cause I feel like I’m on a stronger foundation, but I probably won’t even start work on those courses until after the new year. There’s no way I could’ve known that back in January and there’s no need for me to commit to those dates.

Right? Like that was a soft date in my head. What’s the harm of pushing it out. Okay. I know people are eager and wanting to take those courses. I know I’m taking a revenue hit because I have fewer products in the marketplace, but if I had released them in June, I would have exacerbated the logistical problem having right now in my business.

And what’s going to be better for the long-term growth of my business, cleaning up those underpinnings and then launching on a stronger foundation.

[00:43:01] Janna Bastow: Yeah, that’s exactly right. That’s what I’ve heard. And the way that I differentiate between a hard day to not a soft date is, you know, a true deadline is a date after which if you launch after that date or do something after that date, the value is dropped.

You don’t have any value for doing something after that point, right? Like if you launch something the day after Christmas and you’ve missed the Christmas rush and like, well, what was the point? Right? Like that’s too bad. Maybe we’ll get the value next year. But, most of the time we don’t have those types of things we’re continuously updating.

And so one of the things that product managers can do best is create a space within our company and advocate for continuous deployment, continuous integration, a space where we can regularly get tests out and get insights back from those tests, so that hitting a particular delivery date.

Isn’t really painful, like pulling teeth to get the release out on time, just because the release has to be this particular date. So don’t inflict hard due dates on ourselves, cause sometimes they will be inflicted on us, but we don’t have to inflict them on ourselves. We can try to minimize them.

[00:44:04] Teresa Torres: And I think in a lot of companies, soft dates are treated like hard dates. Like if you miss them, you’re punished, you’re seen as failure. And I think that’s why dates get a bad rap. I think soft dates are a really important tool in our toolbox, but they have to be supported by a culture of, this is not a hard date.

[00:44:23] Janna Bastow: Right. So I’ve got a question here. Somebody says that they get push back when they’re explaining these ideas of continuous discovery, what’s the developer’s role in all this?

[00:44:33] Teresa Torres: Let’s see if we can pick this apart. So I want to start with this idea with scrum, where this is idea that the sprint is sacred, right?

So you’re creating two weeks, most of the time of user stories, and then it’s locked down and you can’t change anything during that sprint. I get why that was part of the scrum process because we saw stakeholders constantly changing requirements. I think it’s baloney. If you learn something that tells you you’re not building the right thing, you should not spend another day building that thing.

So that’s the first thing we got to let go of that. But don’t let this pendulum swing so far the other way, which is where we were before, which was people just change things, willy nilly based on their whim. That’s definitely not what I’m saying. If you learn something from your discovery from customers and you start to recognize what you’re building is the wrong thing, you should stop building it, regardless of whether you’re in the middle of a sprint or not.

So that’s the first thing, does discovery happen ahead of this sprint? This is a really hard question to answer because it’s really rooted in a project world. And I don’t remember how to think in a project world anymore. When your discovery and your delivery are truly continuous, there isn’t a discovery phase in a delivery phase.

I tried to give an example of this in the book. So in the book I tell the story of I was working at a startup. They were a job board for new college grads, or they worked like every other job board where on the homepage it said, what type of job do you want? Where do you want to live? The problem with that is for a 22 year old, fresh out of college, they don’t know how to answer either one of those questions.

So what we wanted to do was we wanted to build an interface where they could just tell us, where did you go to school? What did you study? When are you graduating? And we were going to put a machine learning algorithm behind it to match jobs to them because they just didn’t have the knowledge of what types of job titles were available.

We had this idea, we learned it from interviews. We learned from interviews that students didn’t, or they wanted to live. They didn’t know what type of job they wanted. And so by the end of the, it was literally like my week, one of working at the company. And by the end of week, one working at the company, I was sitting down with our engineers and I was like, What would it take to test an idea like this?

We didn’t have a single engineer who had a machine learning background, not a single one. And everybody was like, we have no idea. And I was like, okay. But really what I want to test is the interface is that if we ask students to tell us what they studied and where they went to school, will they engage with our job recommendations?

So we needed a way to prototype responses to that entry point. Right? Where did you go to school? What did you study? How do we show them jobs? Here’s what we do. We literally spent the weekend taking our list of majors areas of study in our program and generating ourselves can’t keyword searches for every single measure, because we as working professionals and the ability to Google and use Wikipedia could construct a better search query than the average 22 year old, who literally doesn’t even know where to begin.

So we literally spent a weekend re researching, like what kinds of jobs do economics majors get and what kind of jobs do English majors get? And we created these canned searches. And then we on like a Monday or Tuesday, we launched, we split our traffic and had a percentage of our traffic go to this other homepage where we just ran a canvas search in the background.

Here’s what this allowed us to do and allows us to learn well, more people start their search in this new interface and this other interface, will they even engage with the job listings? Because like they didn’t pick those two. It worked. We saw amazing results on our old homepage. We had like 35% of people start a search because most people didn’t know how to answer those questions.

On the new homepage. We saw 85% of people are, those numbers might not be exactly right, but roughly start their search. Okay. Where did discovery start and delivery start? I don’t know. We have a production product. Is it production quality? No, but we have a production product. We have real traffic engaging with our prototype and we’re collecting data.

We had a product in production. I have no idea where discovery started and ended and where delivery started and ended. And here’s what I do know. We started with a teeny tiny piece of value changed the way you start your search. And we found a way to test it in a couple of days. What did we do from there? We iterated on it.

We were like, okay. We can’t rely on canned searches forever. What’s our crudest algorithm we can put behind. And we literally like, we had our fresh out of University of Washington, math major start learning about machine learning. And he started doing all these like machine learning contests, trying to build his chops.

And he started working on like the crudest algorithm that we could put behind it. And we split our traffic. We still split our traffic between our old homepage, our new homepage. On the new home page, we split the traffic between our cans searches and the crude machine learning algorithm. And we literally just kept iterating.

There was no line between discovery and delivery, and this is true for most products, when you get to a continuous cadence, your assumption tests might start in prototypes and surveys and data mining, but eventually they’re going to iterate to live production tests.

So I don’t know how to answer this question. I just think it’s all the same work.

[00:49:56] Janna Bastow: Yeah, I think that’s a really good point. And you know what, it comes down to the process itself and how the team is working and one of the things that I’ve always done to approach that is, think about the process as a product itself. Like you’ve got a process, it’s the starting point.

We’ll treat it like a product, something that you can learn from and measure and iterate upon and improve, right? So each time that you work with the team, each retro that you do—retros are hugely important—you can improve on it and get better and better. And, over time your team can move from being more delivery focused and into being more discovery focused and get this blended approach that Teresa talks about.

[00:50:38] Teresa Torres: We’ll share, like I know most teams work in a project world, even if they’re doing scrum. So what I would recommend is, if you have to start by doing the discovery first in a sprint ahead, and then do the delivery, just keep working to close the gap between those activities.

[00:50:54] Janna Bastow: Yeah, that’s a really good point. Teresa, thank you so much for answering these questions and going into so much detail. I really appreciate that. I want to give a quick shout out for anybody who hasn’t picked up Teresa’s book. Definitely grab yourself a copy, I’ve got one here.

Thank you all for joining us. This session was recorded and will be going up on our YouTube channel.

Teresa, thank you so much for joining us here today. Really good to have a chat about this and I look forward to the next time we get a chance to connect.

[00:51:22] Teresa Torres: Yeah. Thank you so much for having me the hour flew by!

[00:51:25] Janna Bastow: It did. Yeah, absolutely. Thank you all. Have a great day, morning, afternoon, wherever you are and talk to you all later.

Watch more of our Product Expert webinars

How to Build and Manage AI Products and Features

Watch ProdPad Co-Founder and CTO, Simon Cast, for a deep dive into the practicalities of building AI products and features, whether you’re enhancing an existing product or launching something entirely new.

How to Master the Modern Product Manager Hiring Process with Lewis C. Lin

Watch Lewis C. Lin, renowned interview coach and author, and host Janna Bastow as they unpack key changes in PM hiring and offer frameworks, insights, and tactical advice for navigating it all.

How Radical Product Thinking Can Transform the Way You Build Products

Watch Radhika Dutt, Founder of Radical Product Thinking, and host, Janna Bastow, CEO of ProdPad as they share how to break free from iteration cycles and focus on vision-driven product development.

How to Run a Product Launch: A GTM Guide for Product Managers

Watch Julie Hammers, Head of Product at ProdPad, and Megan Saker, Chief Marketing Officer, as they break down exactly how to lead the GTM process with confidence and run a successful launch.