Definition of Ready

What is a Definition of Ready?

A Definition of Ready is a shared checklist of criteria that a backlog item must meet before a team commits to starting it. It clarifies scope, outcomes, risks, and dependencies, aligns stakeholders on what “ready” means, and prevents half-baked work from entering delivery, improving flow, predictability, and quality.

Most teams treat the Definition of Ready as a pre-flight check for development. That’s useful, but it’s not enough. If you want your efforts to actually land, your Definition of Ready must consider the whole path to value: discovery signal, measurable outcomes, analytics, enablement, and go-to-market readiness. Anything less is just checklist theater.

Why is a Definition of Ready important?

A strong Definition of Ready helps teams avoid wasted effort. It stops unclear or half-baked work from sneaking into development, where it would otherwise stall, cause rework, or frustrate the team. When “ready” really means ready, you get smoother sprints, fewer surprises, and less thrash.

Done right, it also reduces rework, stabilizes team velocity, and builds trust with stakeholders. Most importantly, it reinforces an outcomes mindset instead of a shipping features mindset, making sure you know why you’re doing the work and how you’ll measure its success.

- It improves flow by keeping half-cooked items out of sprints.

- It improves quality by forcing clarity on acceptance criteria and risks.

- It improves alignment by making Marketing, Sales, Success, and Support true partners, not afterthoughts.

What should be included in a Definition of Ready checklist?

Think of the Definition of Ready checklist as a toolkit, not a rulebook. It gives your team a foundation to build from, but the actual items should flex depending on the scope of the work, the type of product, and the risks involved. A checklist for a quick SaaS feature release will look different from one for an enterprise workflow change or a regulated-market rollout.

The important part is that it’s a shared artifact. Everyone involved (Product, Engineering, Design, Marketing, Support) should treat it as a living agreement that evolves as you learn more about the work and your customers. Start with this template, then adapt it to your context. Keep it short, clear, and focused on outcomes. Each bullet should be a simple yes/no, not an essay. Keep it visible. Review it often.

1) Problem, outcomes, and scope

Every item should be anchored to a real problem and a measurable result. Without that, you’re just adding noise to the backlog.

- The problem to solve is defined and linked to evidence from Product Discovery. This ensures you’re not just moving forward on assumptions, but on validated insights.

- The target outcome is explicit, with a success metric and timeframe, using the language of Outcomes. This gives the team a clear signal for what success actually looks like. For example, this might be written: “This new video feature will increase our DAU and lift video creation by 15% by next quarter.”

- The scope boundaries and non-goals are clear, so stakeholders know not only what’s included but also what’s deliberately being left out. That prevents endless scope creep and forces tough choices up front.

2) Evidence from discovery

No discovery, no delivery. Even a thin slice of evidence is better than gut feel. If you can’t point to real data or user input, the work isn’t ready.

- User insight is captured, whether through interviews, support tickets, or feedback from your Customer Feedback Loop. This grounds the work in actual user needs instead of assumptions, echoing the principles of Continuous Discovery Habits championed by Teresa Torres.

- Assumptions and risks are listed, with a plan to test the riskiest ones first. Framing these as a Product Hypothesis keeps the team focused on learning rather than blind execution.

- Experiments are considered if uncertainty is high. Not every item needs a prototype or A/B test, but risky bets should prove themselves before they’re allowed into delivery.

3) Readable, testable story or slice

If the team can’t read it, discuss it, and imagine testing it, then it’s not ready. Every item should be small enough to grasp quickly and clear enough that anyone on the team can explain what success looks like.

- A User Story or equivalent format is written concisely and framed around delivering value to the user. Applying the INVEST criteria can help keep stories independent, negotiable, valuable, estimable, small, and testable.

- Acceptance Criteria are defined, testable, and unambiguous — no room for “we’ll know it when we see it.”

- The work is sliced small enough to fit comfortably within your planning horizon, whether that’s a sprint, release cycle, or milestone. Smaller slices mean faster feedback and fewer surprises.

4) Dependencies and integration

Dependencies are where plans go to die if you don’t surface them early. A “ready” item needs a clear map of what it touches and who else is involved.

- Tech dependencies are identified and integration points documented, ideally captured in your Dependency Management process.

- Cross-team coordination is agreed if platform or shared components are affected, so no one is surprised downstream.

- Data, privacy, and security impacts are reviewed if relevant — skipping this can derail releases late in the game.

5) Instrumentation and measurement

If you can’t measure it, you can’t learn from it. Define how success will be tracked before a single line of code is written.

- Analytics events are defined, owners assigned, and dashboards planned so the team knows what will be measured and by whom.

- Baseline and target metrics are captured with a timeframe for review, ensuring you know where you’re starting and what change you expect.

- A rollback plan is considered in case the change negatively impacts key metrics, drawing on your Rollback Plan process.

6) Enablement and go-to-market readiness

Being “dev-ready” is not the same as being “value-ready.” You don’t need polished launch assets before development begins, but you should at least have a plan for how the release will land.

- Release plan and feature flag strategy drafted, using practices like Feature Flags and Release Management to stage rollouts and reduce risk.

- Early enablement prep started — draft messaging themes, FAQs, or training needs identified — so Marketing, Support, and Sales aren’t caught off guard later.

- Ownership agreed for creating customer-facing assets and internal briefings before launch.

7) Compliance and governance

Not every team needs this, but in enterprise and regulated contexts it’s essential. A Definition of Ready should surface compliance needs early so they don’t derail a release at the last minute.

- Accessibility, legal, privacy, and security reviews are scoped and scheduled when the work requires them.

- Sign-offs are defined with clear SLAs, so approvals don’t become a last-minute scramble.

A Definition of Ready checklist isn’t about bureaucracy. It’s about giving your team confidence that when they pick something up, it’s genuinely startable. The template gives you a solid foundation, but the magic comes from adapting it to your reality and keeping it alive. Treat it as a tool for clarity, not a hoop to jump through.

Tip: Keep your Definition of Ready to 10–14 short, clear checks. If it takes a meeting to explain the checklist itself, you’ve accidentally built a process to support a process.

When everyone knows what “ready” means, you avoid thrash, reduce rework, and set the stage for smoother, more impactful delivery.

How do you create a Definition of Ready with your team?

Treat your Definition of Ready as a working agreement, not a contract. The point is to align on what “ready” means so the team can start with confidence and finish without surprises. Build it together in a facilitated session with Engineering, Design, Product, Marketing, Support, and QA. When everyone has a hand in shaping it, everyone has a stake in using it.

Here’s how to co-create a Definition of Ready that actually works:

- Start with outcomes. Ask, “What do we need to know to be confident this work will move our key metrics?” Tie every checklist item back to that purpose.

- Mine your history. Look at your last five painful incidents, rollbacks, or stalled stories. What was missing before you started? Promote those gaps into DoR checks.

- Right-size for your context. Enterprise teams may add compliance steps. Startups may keep it leaner, biasing toward speed with fewer checks but stronger experiment gates.

- Pilot and iterate. Apply the draft DoR to one squad for a sprint or two. Remove checks no one uses, clarify what’s ambiguous, and add anything you missed. Keep refining.

- Make it visible. Embed your DoR where the work actually happens — in your idea template, story format, refinement checklist, or roadmap items. Don’t leave it buried in a wiki no one reads.

- Revisit in retros. When half-baked work slips into sprints, don’t pile on more process by default. Instead, ask: “Which single DoR check would have prevented this?”

When you create your Definition of Ready as a shared agreement, it sets your team up to start strong and finish without surprises. But don’t treat it as fixed. A good DoR should evolve alongside your product. If it hasn’t changed in six months, that’s a red flag you’re not learning enough from your own process.

What’s the difference between Definition of Ready and Definition of Done?

The Definition of Ready and the Definition of Done are often confused, but they play very different roles in product and development processes. Understanding the distinction is critical if you want smoother delivery and fewer surprises.

- The Definition of Ready sets the criteria for entry into development. It asks: “Do we fully understand the problem, the outcomes we want, the scope, and the risks well enough to start building?” If the answer is no, the work isn’t ready.

- The Definition of Done sets the criteria for exit from development. It asks: “Does this piece of work meet our agreed quality bar, including tests, documentation, and acceptance criteria?” See Definition of Done.

A simple way to remember the difference: the Definition of Ready reduces risk before commitment, while the Definition of Done ensures quality before completion. You need both. Without a Definition of Ready, teams commit to unclear work and invite rework. Without a Definition of Done, teams ship half-finished or low-quality features that erode trust with users.

Not sure if your process is set up for outcomes, not just outputs? Try the Interactive Sandbox to see how ProdPad connects discovery, ideas, and delivery into a single flow.

Common mistakes and misconceptions about the Definition of Ready

The Definition of Ready is meant to create clarity and confidence, but when misapplied it can slow teams down or undermine agility. These are the most frequent pitfalls to avoid:

Mistake 1: Treating the Definition of Ready as a gate to protect Engineering from Product

The Definition of Ready is not a moat around the development team. It is a shared agreement that protects the entire business from wasting effort on unclear work. If it becomes the responsibility of a single function, it risks turning into a weaponized process.

Mistake 2: Equating “ready” with “fully specified”

Over-specifying to feel safe simply moves waste earlier in the process. Effective teams clarify the outcome and the constraints, then slice the work thin and learn early. Acceptance criteria should set boundaries, not serve as lengthy documentation.

Mistake 3: Ignoring go-to-market readiness

If Support, Sales, or Marketing only discover a change when release notes are published, the work was never truly ready. Readiness includes ensuring that customers will understand it, internal teams can explain it, and success will be measured. See General Availability (GA).

Mistake 4: Turning the Definition of Ready into paperwork

A checklist that takes 45 minutes to complete defeats the purpose. A good Definition of Ready is short and impactful. Automate where possible and focus only on checks that genuinely change outcomes.

Mistake 5: Applying one Definition of Ready to all teams

Different teams need different readiness criteria. A platform team, a growth team, and a regulated-market team will not share the same requirements. Maintain a core set of checks and allow teams to add three to five context-specific items.

Mistake 6: Believing the Definition of Ready is anti-Agile

Agility is about fast feedback and adaptability. A well-applied Definition of Ready increases agility by reducing thrash and making work sliceable. A poorly applied one can block learning. The tool itself is not the problem — how it is used makes the difference.

Who is responsible for the Definition of Ready?

Ownership of the Definition of Ready often differs across organizations. In some cases it sits with the product triad (Product, Design, and Engineering) as a joint working agreement. In others, Engineering may take the lead, particularly if the DoR is treated as a technical quality gate.

What matters most is that ownership is explicit and shared, so items don’t stall in the process. Many teams use decision-making frameworks like DACI (Driver, Approver, Contributors, Informed) or ARPA (Accountable, Responsible, Participant, Advisor) to clarify roles. This ensures the DoR evolves without bottlenecks and that everyone knows their part in keeping it current.

Here’s an example of how a DACI for a Definition of Ready might look:

| Role | Example Owner | Responsibility |

| Driver | Product Manager | Facilitates updates to the checklist and ensures items are prepared before sprint planning. |

| Approver | Engineering Lead | Signs off that items meet the technical bar and can move into development. |

| Contributors | Design, QA, Marketing, Support | Provide input on usability, quality checks, customer impact, and enablement needs. |

| Informed | Stakeholders, Leadership | Kept updated on changes to the checklist or process but not directly involved. |

A healthy DoR is never “owned” by one role alone — it works best when it reflects cross-functional alignment and is actively maintained by the people who use it.

How do you keep your Definition of Ready useful over time?

Your product changes, your team evolves, and so should your Definition of Ready. A checklist that stays the same forever quickly becomes stale and stops adding value. To keep your DoR relevant and effective, treat it as a living artifact and revisit it regularly.

- Track leading indicators. Watch for work items that routinely fail in delivery and trace them back to missing DoR checks. Tighten the checklist where it prevents repeat mistakes, and loosen it where it’s adding no value.

- Time-box refinement. If “getting items ready” starts taking over refinement sessions or sprint planning, cap the prep time and slice the work smaller instead. A Definition of Ready is meant to streamline these meetings, not consume them.

- Run DoR audits. Once a quarter, sample 10 completed items and score adherence. Use what you learn to improve the checklist itself — fix the template, not the people.

- Automate where possible. Pre-fill fields, link to discovery evidence, and embed the checklist directly into your story or idea template. The best checks are completed naturally as part of the work, not in parallel.

- Teach outcomes. Tie every DoR item back to a clear outcome. People are more likely to uphold processes when they see how those checks connect directly to success.

How does the Definition of Ready connect to outcomes and roadmaps?

This is where many teams miss the bigger picture. A Definition of Ready shouldn’t just guard the sprint backlog — it should tie your roadmap, backlog, and outcomes together, making sure every piece of work contributes to strategy and value.

- Each roadmap initiative should declare a clear outcome and spell out how ideas underneath it will be considered “ready.”

- Each idea should carry a simple product hypothesis along with evidence from discovery, so you know why it’s worth investing in.

- Each release should include instrumentation and measurement, as covered in release planning, to prove whether the work actually moved the metric it claimed.

Handled this way, the Definition of Ready isn’t just a checklist for developers. It becomes the connective tissue from strategy to shipped value, ensuring every backlog item has a line of sight back to outcomes.

“Curious how to connect readiness with measurable results? Download our 25 Ready-made Product OKRs and tie your checklist to outcomes.”

Curious how to connect readiness with measurable results? Download our 25 Ready-made Product OKRs and tie your checklist to outcomes.

How ProdPad supports a stronger Definition of Ready

ProdPad is built to anchor teams in outcomes, not just output. If you want your Definition of Ready to be more than a laminated poster on the wall, it needs to live where you plan and make decisions. ProdPad provides that context:

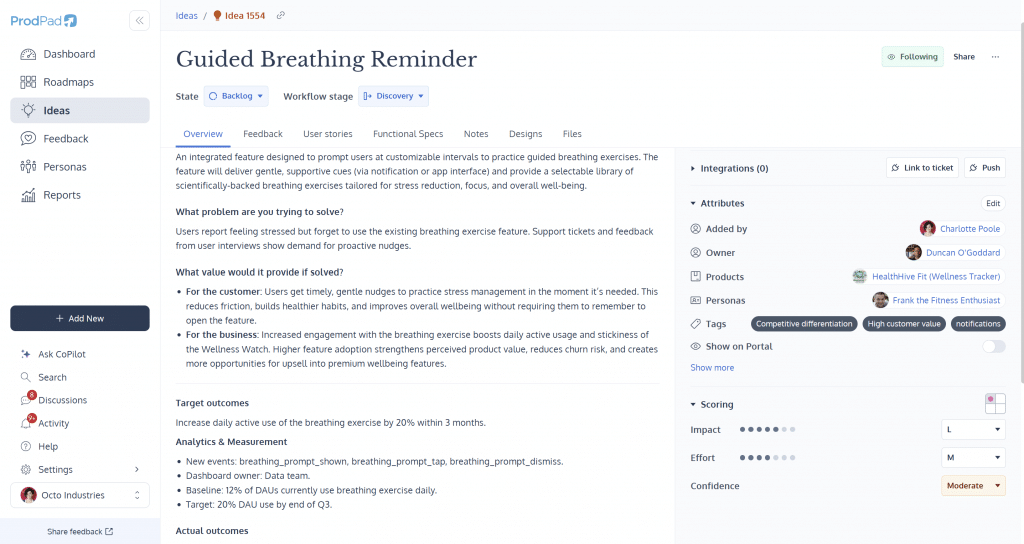

- Ideas and hypotheses: Capture the problem, target outcome, assumptions, and linked feedback in a single record, complete with acceptance criteria and context.

- Outcome-driven roadmaps: Use the Now/Next/Later format to shape initiatives around problems and results, not arbitrary dates or feature wish lists.

- Feedback and evidence: Centralize customer signals so every “ready” item connects back to a real user need, not just an internal hunch.

- Release hygiene: Tie rollout plans, feature flags, and measurement directly to the item, so you can close the loop when metrics come in.

Make “Ready” actually mean ready

If your Definition of Ready only protects the sprint, you will ship on time and still miss the point. The point is impact. Use DoR to guard the path to value, not just the entrance to development. Keep it short. Keep it visible. Change it when reality changes. And most of all, tie every check to an outcome you care about.

When your teams start treating “ready” as “ready to learn” and “ready to create value,” you will feel it. Less thrash. Fewer rollbacks. Better conversations. Clearer decisions. That is the compounding effect of a Definition of Ready that actually does what it says on the tin.

Turn your checklist into impact.

ProdPad helps teams move from half-baked to outcome-ready.