Why Product Teams Don’t Have a Prioritization Problem, They Have a Decision Confidence Problem

Product teams love to say they have a prioritization problem.

I hear it from PMs, Heads of Product, and CPOs. It shows up in retros, roadmap reviews, leadership meetings, and in those quiet moments where someone stares at a backlog that has somehow turned into a museum of every request the business has ever made.

Most of the time, when someone says “we need to get better at prioritization,” what they really mean is:

- We keep changing our minds

- We can’t get stakeholders aligned

- Everything feels important

- We don’t trust the decisions we’re making

- We don’t know how to justify saying no

That’s not a prioritization problem.

That’s a decision confidence problem.

And it matters because when confidence is low, teams reach for false certainty. They reach for scoring models, ranking spreadsheets, and “objective” frameworks because it feels safer than admitting the truth.

Product decisions are bets.

They always have been.

Prioritization frameworks are comforting because they look like certainty

I get why teams reach for frameworks. I really do.

When everything feels important, when stakeholders are pulling in different directions, when you’re under pressure to justify every decision, a framework feels like relief.

A spreadsheet feels calm.

Numbers feel neutral.

Scores feel defensible.

Frameworks promise objectivity. They promise fairness. They promise that if you just follow the process, the right answer will reveal itself.

The problem is that product decisions don’t work like that.

Most product teams don’t need help generating a list. They need help committing to a direction. They need help making the trade-offs explicit and sticking to them long enough to learn something.

That’s what decision confidence actually is.

The illusion of certainty is the real risk

One of the most dangerous things frameworks create is false certainty.

A feature scores higher, so it must be right.

A number is bigger, so it must be more important.

A list is ordered, so the decision must be made.

But the math hides uncertainty instead of surfacing it.

A sharp critique of this shows up in Honest PM’s piece, “RICE Ain’t So Nice”, which lays out why scoring models feel rigorous even when they’re multiplying guesses with wide margins of error.

I’ve seen teams treat a prioritization score as fact, even when their instincts are screaming that something is off.

And I’ve seen the opposite too. Teams adjusting scores until the spreadsheet agrees with what they already believed.

At best, this wastes time.

At worst, it leads teams to build the wrong thing because the spreadsheet said so.

The framework didn’t remove bias. It just hid it.

The inputs are guesses, and that’s fine. Pretending they are not is the problem.

There’s a version of this conversation where someone says, “So you’re saying we shouldn’t estimate?”

No.

Estimation is useful when it’s used as a stake in the ground. It’s helpful when it triggers a conversation like:

- What assumptions are we making?

- What’s driving that “impact” number?

- What would have to be true for this to pay off?

- Where are we likely underestimating effort or risk?

That’s good product work.

The failure mode is when teams start treating estimates as reality. Or worse, treating the model as a replacement for judgment.

Product decisions live in uncertainty. They always have. Trying to eliminate uncertainty with math doesn’t make it go away. It just makes it less visible.

If the spreadsheet is the decision, people will game it

Here’s a predictable human behavior: when a system controls outcomes, people learn how to work the system.

If “what gets built” is determined by a score, then people start optimizing for score. Stakeholders learn which levers to pull. PMs learn which numbers get a project funded. Teams learn which kinds of work are easiest to justify.

This is how you end up with prioritization theater:

- A backlog full of “high impact” items with no evidence

- Everyone suddenly “confident” in their guesses

- A miraculous inflation of reach

- A very convenient collapse of effort estimates

You don’t end up with clarity. You end up with a spreadsheet that looks like clarity.

Sometimes teams even refactor the scoring algorithm itself. Not because the algorithm is wrong, but because it’s disagreeing with what the team already knows is the right thing to do.

That is time spent on the wrong work.

Prioritization is not hard because you can’t identify good ideas

One of the cleanest lines I’ve seen on prioritization comes from product coach Rich Mironov, who bluntly lays out the physics problem underneath it. In “My Next Word to Retire is ‘Prioritization’”, he points out that when you add up the “priority lists” from across an organization, you routinely get 20x to 50x more demand than delivery teams can complete. That means you have to say “not now, not later, not ever” to most requests.

That’s the truth that frameworks try to soften.

You don’t have a ranking problem. You have a refusal-to-say-no problem.

And saying no requires confidence.

When everything is a priority, nothing is

Another pattern I see constantly is teams claiming to have five, ten, or twenty priorities in a quarter.

That’s not prioritization. That’s sequencing. Or more honestly, it’s wishful thinking.

Real prioritization is about focus. It’s about choosing a small number of things to go deep on, knowing that depth is where impact actually comes from.

When organizations avoid trade-offs, you see it in every method. You see it in scoring models, where everything magically scores high. You see it in categorical methods like MoSCoW, where everything becomes a “Must.”

That’s not a MoSCoW problem. That’s an organizational courage problem.

When demand is 20x supply, prioritization becomes a leadership problem

If your organization genuinely has 20x more demand than capacity, then prioritization isn’t a product team problem. It’s a leadership problem.

Mironov makes this point in other places too, including “Permission to Stay Focused”, where he reframes focus as the scarce resource, not ideas.

Decision confidence in product isn’t just the PM feeling confident. It’s the organization being willing to back a decision and accept what it costs.

If leadership reopens decisions every time someone complains loudly enough, product teams learn not to commit. They learn to keep options open, keep everything in the backlog, keep everyone vaguely happy.

That’s how you end up with motion instead of progress.

Decision confidence comes from clarity, not math

Decision confidence comes from a few unglamorous things:

- Clear strategy

- A shared understanding of the problem you’re solving

- Evidence from customers

- Alignment on what success looks like

- Leaders who back the decision long enough to learn

When those things are present, prioritization gets easier.

Not easy. Easier.

The conversation shifts from “what scores highest?” to “what are we optimizing for right now?”

That’s the shift that matters.

Gibson Biddle talks about the habits that support this kind of decision-making in “10 Habits for Making Wicked Hard Decisions”. The point isn’t that you can make decisions perfectly. It’s that you can make them deliberately, with a clear understanding of stakes, reversibility, and what you’re trying to learn.

Decision confidence is not certainty. It’s clarity about the bet.

If decision-making feels chaotic, it’s often because there’s no shared product operating model underneath it.

Use frameworks to start conversations, not end them

I’m not anti-framework. I’m anti outsourcing thinking.

Frameworks are useful when they help teams surface assumptions, challenge each other, and make trade-offs visible.

They’re harmful when they’re used to avoid judgment.

If you want to score ideas to kick off a conversation, great.

If you want to estimate effort to expose risk, great.

If you want to sense-check reach or impact, great.

But the final decision should still be a human one, made in the context of strategy and evidence.

And sometimes that decision should deliberately go against the scores.

If you can’t explain why you’re choosing something without pointing to a number, that’s a smell.

Use scoring to create a stake in the ground. Use judgment to make the call. Get our prioritization guide.

The “real” work is deciding what you’re optimizing for

When teams struggle with prioritization, what they often lack is a stable optimization target.

They don’t have clarity on:

- Which customers they’re choosing

- Which market they’re winning in

- What outcomes matter most this quarter

- What risks they’re willing to accept

So they prioritize based on what is loud. Or escalated. Or political.

Mironov captures this bluntly in “Prioritization Beyond Algorithms”, where he explains that prioritization fits into a larger strategic and organizational context, not a mechanical ROI exercise.

And he’s also been explicit about the politics of it. Product leaders often think prioritization is an analytical problem, while other execs experience it as negotiation and power. That tension is laid out clearly in this guest piece published by Product Focus.

Decision confidence is what keeps product teams from being whiplashed by those dynamics.

Confidence does not mean “never change your mind.” It means “change your mind for a reason, and keep the reasoning visible.”

Case study: when “fair” prioritization still destroys the product

One of the strongest real-world stories I’ve seen on this comes from Michael Goitein in “The One Reason Why Prioritization Frameworks Will Never Work, and What to Do Instead”.

The story is painful because it’s common. A team does “fair” prioritization across stakeholder requests, gradually packs more and more features into a product, and ends up with a bloated experience that stops making sense. Eventually, the product collapses under the weight of it, and the organization has to rebuild.

That’s a failure mode of prioritization frameworks that people rarely talk about.

Even when the process is fair, you can still build nonsense.

Because the framework helped decide between feature requests, but it never forced the higher-level decision: what kind of product are we building, for whom, and what do we refuse to become?

If you prioritize at the wrong level, you can be very efficient at killing your product.

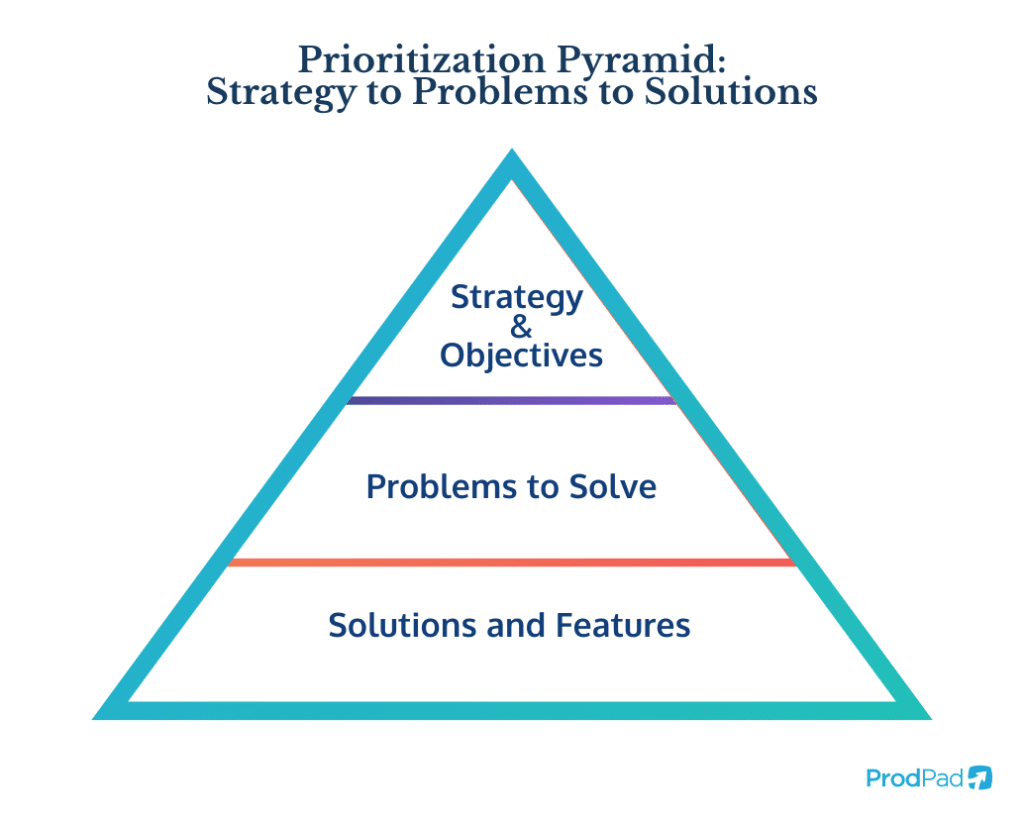

Decide at the right level: problems, not features

Teams get trapped when they prioritize solutions instead of problems.

Saeed Khan says this directly in “Why You Should Avoid Prioritization Frameworks and How To Prioritize The Correct Way”. His point is not “never structure decisions.” It’s that if you have so many “features” to prioritize that you need a spreadsheet to survive, there’s likely a strategy and clarity problem underneath.

This is the decision confidence lever most teams miss.

When you decide which problem you’re solving and why, a lot of feature debates get easier. Options narrow. Trade-offs become visible.

When you don’t, the backlog becomes an argument you never finish.

Why I keep coming back to Now-Next-Later

I created the Now-Next-Later roadmap because timeline roadmaps demand a level of certainty product teams can’t honestly provide.

I’ve written about this directly in “Why I Invented the Now-Next-Later Roadmap”.

Now-Next-Later works because it forces decision confidence without pretending to eliminate uncertainty.

- Now is what we’re confident enough to work on today.

- Next is what we believe comes after, but we are open to changing.

- Later is intentionally vague, because pretending certainty that far out is dishonest.

It creates space to say “this matters now” without overcommitting to everything else. It shifts the conversation away from ranking features and toward sequencing decisions.

What deserves focus now?

What can wait?

What needs more learning before we decide?

That’s the real work of product leadership.

If your roadmap keeps turning into a commitment trap, Now-Next-Later gives you a way to communicate direction without faking certainty.

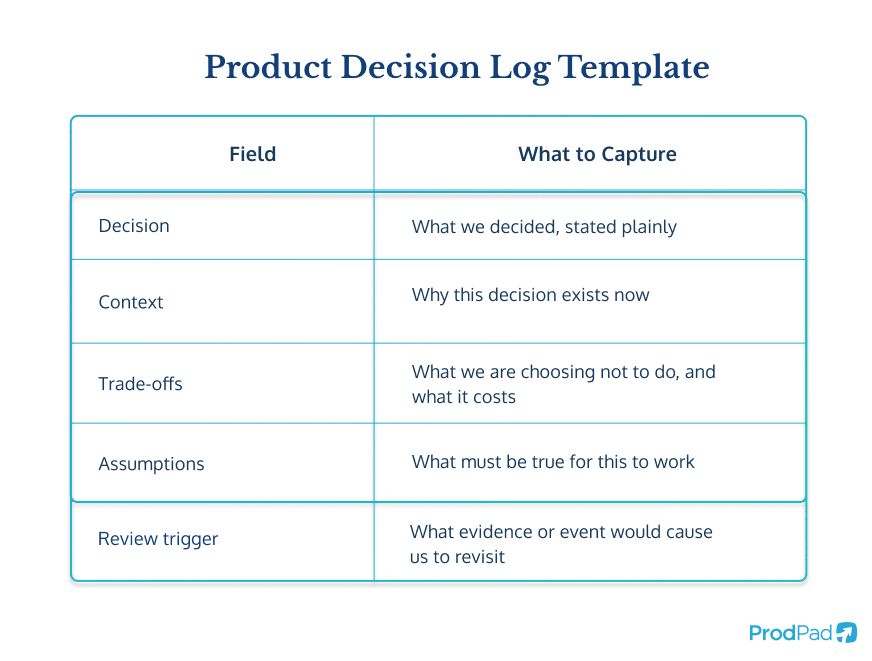

Record decisions so you stop relitigating them

A big chunk of “prioritization pain” is actually decision churn.

The organization makes a call, then forgets why, then changes it, then argues again, then blames product for being inconsistent.

Decision logs sound boring, but they are confidence fuel.

They help you:

- preserve context

- show reasoning

- revisit assumptions

- distinguish learning from thrashing

If your decisions keep getting reopened, a lightweight operating cadence can stop the churn. Check out our guide.

Make it safe to admit uncertainty

Decision confidence is not swagger. It’s not pretending certainty. It’s not bullying the room into alignment.

It’s the ability to move forward with a bet while staying honest about what you know and what you don’t.

Annie Duke nails the nuance in “Communicating Uncertainty and Inspiring Confidence”. The core idea is that you can communicate uncertainty without undermining trust, as long as you’re clear about how you’re thinking and what you’re doing to reduce unknowns.

Product teams often get punished for honesty. Stakeholders demand certainty, teams comply, and then everyone is angry later when reality happens.

Confidence is not certainty. Confidence is clarity about the bet.

The uncomfortable truth

If prioritization feels heavy, it’s rarely because you picked the wrong framework.

It’s usually because:

- the strategy is fuzzy

- the problem is not well understood

- the organization punishes clear decisions

- leadership keeps reopening calls

- or the team is afraid of being wrong

No spreadsheet can fix that.

Decision confidence is built through practice. Through learning. Through making bets and staying with them long enough to see outcomes. Through being allowed to say “we tried, it didn’t work, and here’s what we learned” without the organization treating that as failure.

Product teams don’t need better prioritization tools.

They need the confidence to decide.

Why product needs strategic guts, not more frameworks

A roadmap is a set of choices. Not a list of requests. Not an output of a scoring model.

If prioritization feels hard, it’s often because nobody has named the trade-off yet.

Name the trade-off.

Own it.

Write it down.

Build the decision muscle.

That’s how you get out of prioritization theater and back into product leadership.